UNIT 1

Learning from the Mountain

Geology of the summit area and how people study it.

Activities in this Unit:

- Haleakalā Past and Present

- Haleakalā Detective Work

- The Dating Game

UNIT 2

Summer Every Day and Winter Every Night

Climate of the summit area.

Activities in this Unit:

- What’s the Temperature at the Summit?

- Mauna Lei Mystery

- Summer Every Day and Winter Every Night

UNIT 3

Life in the Kuahiwi and Kuamauna Zones

Native and introduced species, relationships, and adaptations.

Activities in this Unit:

- Alpine/Aeolian Challenges and Adaptations

- Holding on to Water Lab

- Adaptations Game Show

- Web of Life Game

UNIT 5

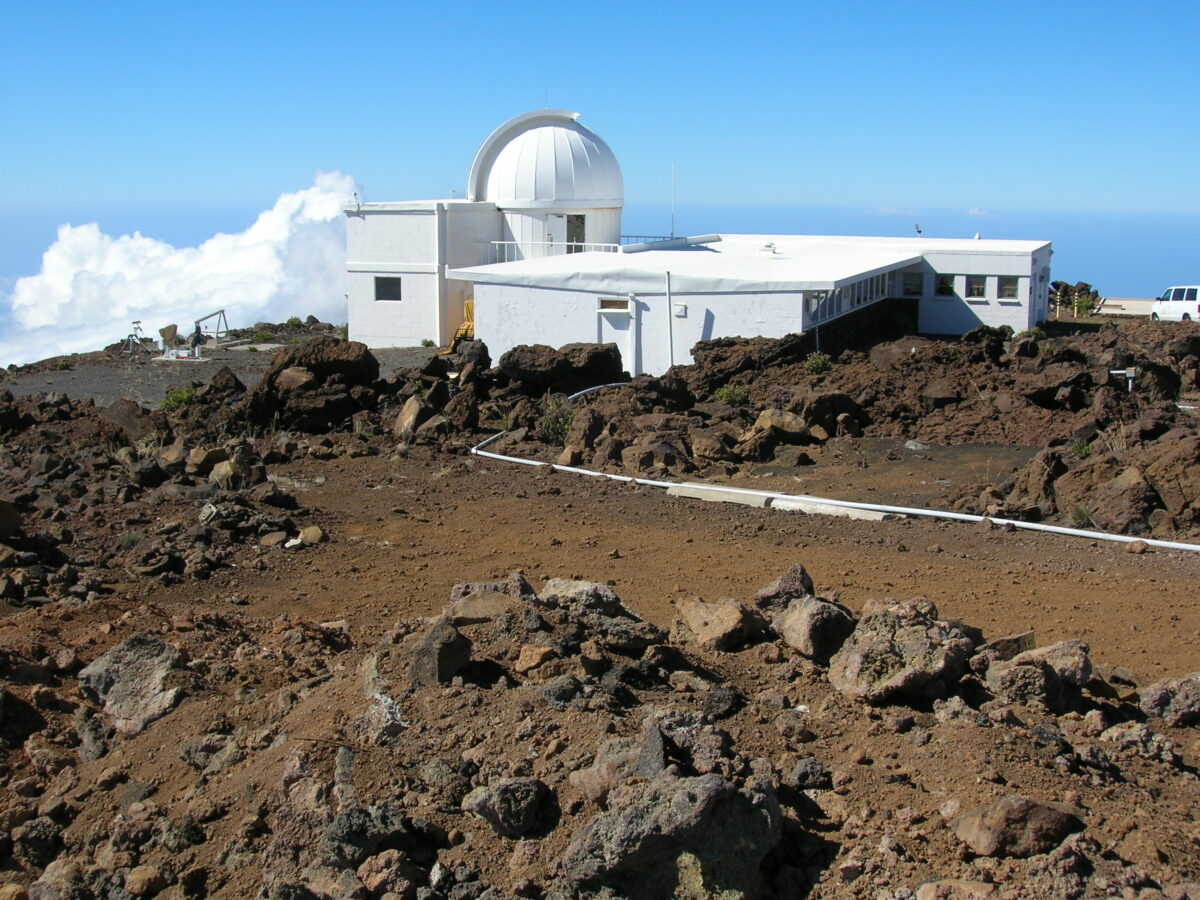

Observatories, Transmitters, & Sacred Places

A contemporary issue revolving around the significance and use of the summit area.

Activities in this Unit:

- Exploring the Importance of the Summit

- In-Class Public Forum

- What Goes on at the Observatories

What does the Alpine / Aeolian Zone Mean to You?

These reflections are offered by individuals involved in studying and protecting the native ecosystems of Haleakalā.

“House of the sun, house of the snow. Silverswords.”

—Kim Martz and Forest Starr

“Sacred elder, the piko of East Maui. The wind blowing my hair.”

—Kalei Tsuha

“Looking up at Red Hill or gazing down into that vast expanse of the crater, it’s easy to get the impression that the place is lifeless. There is more than meets the eye in this great depression of Haleakalā. The more you look, the more you see.”

—Betsy Gagné

“From here, one can only look up to the heavens, to the edge of our existence. Every day, for those who inhabit this ecosystem, the edge of life and death is as razor-thin as the distant horizon. Here, two worlds can collide: The warmth of the sun and the fire of the Earth!”

—Eric Andersen

Where on Haleakalā?

The alpine/aeolian ecosystem is located above 2300 meters (7544 feet) elevation in the cinder- dominated summit basin; above 2600 meters (8528 feet) on the older western, outer slopes of the summit basin. It extends to the summit at 3056 meters (10,023 feet).

Basic Characteristics

This high-altitude region is characterized by sparse vegetation (generally 0-5% cover), scarce food sources for insects and other animals, generally dry conditions, and an extreme climate with widely varying daily temperatures and intense solar radiation.

Did You Know?

Aeolian is a term first used in 1963 by L.W. Swan to describe communities of insects that survive on high-elevation landscapes of snowfields and barren rock. These systems, where little vegetation grows, are fueled primarily by organic matter blown in on the winds. These systems are appropriately named after Aeolius, Greek god of the wind.

On Haleakalā, a unique collection of arthropods (the family that includes spiders, insects, and centipedes) has evolved to take advantage of the insect life and plant matter that is blown in by the upslope winds.

Status and Threats

The alpine/aeolian is perhaps the most intact ecosystem type on Maui. Most of its historic extent has been maintained through more than 1500 years of human contact. Until recently, this environment has been little influenced by nonnative species, and the native insect fauna is still nearly intact.

For many years, vegetation in this zone was damaged by feral goats. Much vegetation has recovered following the erection of protective fencing and the removal of the goats.

Ants, rodents, and nonnative parasitic insects threaten native insects and the plants with which they coexist. Careful management of the increasingly popular Haleakalā National Park (which encompasses 50-60 percent of the alpine/aeolian ecosystem on Maui) is necessary to protect this nearly intact system, since human activities tend to expand the range of nonnative species. Activities linked with observatories and communications structures in the summit area must also be managed carefully.

Traditional Hawaiian Significance

Keen observers of the islands’ natural communities, early Hawaiians identified twelve life zones that stretched from makai to mauka. Haleakalā and the surrounding ocean encompass all of these zones, many of which have been dramatically changed by human use. At the top of Haleakalā, however, are two zones where the natural communities are still largely intact the kuahiwi (backbone) and kuamauna (back mountain). These zones comprise what we know as the alpine/aeolian ecosystem.

In the traditional system of dividing the Hawaiian Islands into political regions, the ahupua’a was the most important land division. Ahupua’a usually extended from these upper reaches of the mountains to the outer edge of the reef in the ocean, cutting through all of the major environmental zones along the way. Each ahupua’a encompassed most of the resources Hawaiians required for survival, from fresh water to wild and cultivated plants, to land and sea creatures. Because of their dependence on the land’s resources, the Hawaiians developed a complex system of resource management and conservation that could sustain those resources over time. This system was tied intimately to the religious and cultural beliefs of the Hawaiian people.

In Hawaiian tradition, the upper reaches of the mountain are the sacred House of the Sun (a literal meaning of Haleakalā), where every day begins. Today, people still visit the summit just to see the moment when the sun rises above the distant horizon. This is the place where the demigod Māui snared the sun to slow its passage across the sky and make it easier for his mother to dry her kapa cloth.

At the height of Hawaiian society, this gathering place of the gods was visited by few people. Kāhuna, Hawaiian spiritual leaders and elders, went there for meditation and to receive spiritual information. The kilo hōkū (astronomers) brought young men training to be navigators up the mountain to teach them about the sky and the stars. Important people were buried up there, and there is a place where people buried the piko (umbilical cords) of their babies.

Hawaiians constructed shelters in the summit area, but no one lived there. Workers came to quarry rocks for making adzes and other tools. Hunters came to hunt ‘ua’u (petrels) for food. Travelers sometimes passed through while crossing from one side of the island to the other and perhaps stopped to collect a gift such as a bird feather before continuing on.

Before going to the summit of Haleakalā, Hawaiians had to ask permission from human authorities and from the gods. Among those who were given permission to enter this sacred place were men who quarried basalt rock for making adzes and other tools. Today, many Hawaiians continue to pray for permission before they go to the summit. This area is no less sacred today than it was in times past.

Journal Ideas

Use some or all of the following topics for student journal entries:

- Listen to the chant as it is read in Hawaiian. How would you describe the feeling of the chant? What did it make you think about?

- Listen to the English translation of the chant. Do you have different thoughts and feelings now that you know what this chant means in English?

- Have you ever been to the top of Haleakalā? What are your impressions of this area?

- If you haven’t been to the summit, whom do you know who has been? What do you think that person saw and felt like up at the top of Haleakalā?

Search Curriculum by Activity

Use our grid below to search for a specific activity by unit, type, or topic.